Redux: Everyone is doing as well as they can

Revitalizing this post for the 2024 U.S. election aftermath

A lot of people are upset about the 2024 U.S. election.1

It was like this for me leading up to the 2016 election. The candidate I really believed in during the primaries—not only his stated policies but his professional track record, and his presence in-person—was undemocratically swept aside by the power brokers of the Democratic party.

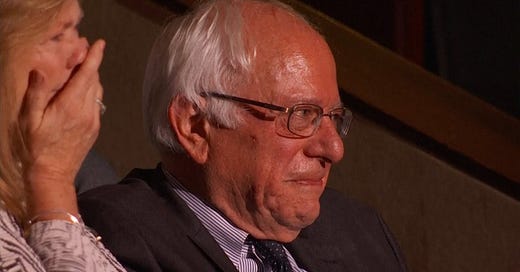

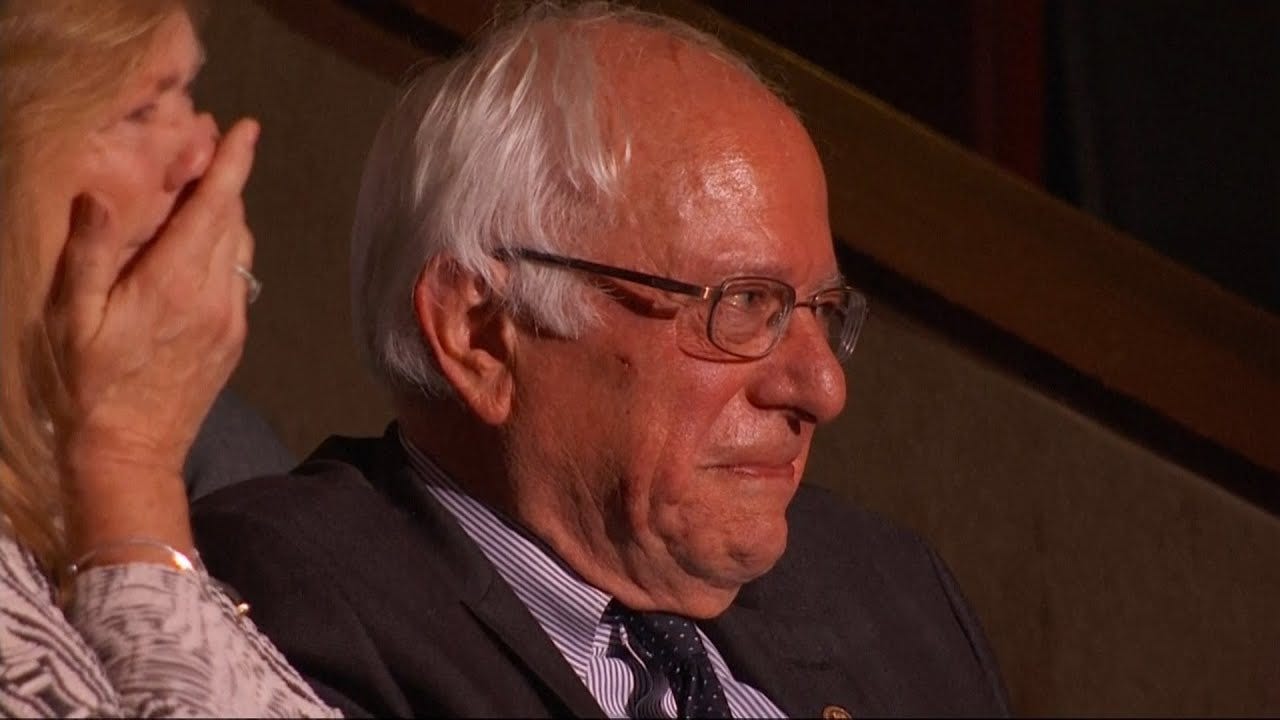

It was this exact moment right here at the 2016 Democratic National Convention when I knew I was done with this whole farce. Not just this election—done with large-scale American politics in general. Anyone I felt was worth supporting could not win. I felt the ember in my heart quench, and my mind, like a popped incandescent lightbulb, filled with furious tendrils of smoke.

From then on, I related to the U.S. presidential elections as natural disasters. Lumbering monsters with a thousand faces trailing hypnotized mobs, dragging themselves across the country.

I’ve stated often, with a kind of sadistic pleasure, that at the conclusion of every election Americans have the representation we deserve.

I resented the high-level politicians, of course—our reptilian aristocracy. But I resented the U.S. public most of all. The voters and those abstaining. We could be living in a semi-utopia, my kind of semi-utopia, but for the idiocy of these fools crawling around on this rock with me. And I resented myself for caring. I knew I was a sucker, knew politicians and their campaign donors were working to pull at my heartstrings for personal profit.

And yet I couldn’t help it. Even if I didn’t participate, even if I elected only to cast votes for local decisions during the elections, I cared. I was moved by political argumentation, by the stories politicians told, and I saw my mind play host to whatever political memes circulated at the time.

This all has not really changed with this election. It’s possible that I may find another presidential candidate worth supporting wholeheartedly again, but probably not. My degree of support in 2016 certainly had a lot to do with the 26 year-old eyes I saw the situation through.

Something else has changed over the last few years.

I no longer feel my heart hardened against the people involved in this process, affiliated with any political candidate or not. I realize now, in a visceral way, that everybody is trying their best. I don’t mean everyone is living up to my fantasy of their personal potential or some ideal I have about how everybody should act.

I mean, for the situations people actually find themselves in, moment-by-moment, everyone is doing as well as they can. Let’s explore what that means.

We are always spontaneously patterning toward benefit

Every second of every day of our lives, we think, feel, and act towards the greatest available benefit. Our perception patterns itself according to what seems most worthy of care at that moment. This can happen with rigid fixation, or it can be fluid.

For example, maybe we have maintained largely the same daily routine for the last ten years. We wake, take coffee while looking at social media, get ready for work, commute, work, commute, eat dinner while watching TV, scroll social media some more, get ready for bed, and go to sleep. At some point, each of these activities has been the most obvious thing worth caring about. Otherwise, we would never have engaged with them in the first place.

Even if we feel bad about some part of our daily routine, like scrolling social media for one to two hours per day, we turn to that activity because it feels like the most obvious thing worth caring about in the moment.

This may because it seems to help regulate our emotional state, like going from a state characterized by boredom to a state characterized by absorbed attention. We don’t feel so good (boredom) and by taking this familiar action (scrolling), we address that personal concern. At least in the most obvious way, we have created benefit (changing to a more preferable emotional state) to the greatest degree (for one person—ourselves) that seems available at that moment.

Maybe, throughout the day, we think about doing something different. Maybe we want to work a gym membership into our daily routine. We feel like we’re doing something wrong—not being healthy enough, not living up to the potential of our physical aesthetics—or we simply feel like we could be happier, if we made a change. That desire for change is also our perception patterning towards benefit.

We care about what we perceive, and we act based on that care.

That doesn’t mean we act in a way that aligns with our intellectual ideals. Maybe, feeling care arise in the form of concern about our long-term health, we feel the affordance of reaching for our phone and scrolling social media. This act has a proven track record of adjusting our emotional state by presenting a procession of objects in which we can absorb our attention.

In any case, our perception patterns itself with care, creating benefit to the greatest possible degree afforded by that moment.

When we feel bad, we may behave in all sorts of funny ways because feeling fractionally better for a few moments is the greatest apparent benefit available. Scrolling social media on our phone isn’t going to improve our health, but the concern we feel2 can be addressed by this familiar method. The same applies when our anger boils over and we find ourselves shouting at another driver in traffic, when we narrowly avoid a fatal accident that would have been their fault. Or when we berate our uncle at Thanksgiving for having a political affiliation that is obviously morally incorrect.

There is no end to the actions we take in moments like these that we may later regard as terrible mistakes. But even our greatest mistakes are avenues we take toward the greatest benefit that seems possible to us at that moment.

Altruism is the intellectual version of patterning towards benefit.

Speaking of acting in ways that aligns with our intellectual ideals, we may believe that we are (or we should be) working with altruistic intent to benefit the greatest number of people possible. Realistically, we may investigate our mind’s activity and discover the area of effect is relatively small, actually.

Maybe we’re engaging in altruism (or believe this would be a good idea) because we think it will make us feel better, based on how altruistic activity has made us feel in the past.

There is nothing inherently wrong with this. But it’s worth noting how often acting according to intellectual ideals fails to create the utopian conditions those ideals aim toward. When we have very rigid perception because we slavishly adhere to an intellectual ideal, the potential for causing harm to ourselves and others is especially great.

Rigid perception leads to stale patterns of care-full activity

The less flexible our perception is, the more rigidly patterned our care is likely to be. Constraint here means an apparent lack of available motion. The paths toward benefit, when perception is highly constrained, are likely to be very short indeed. These will lead to highly familiar destinations, like a phone screen, a refrigerator, a video game controller, a vape pen, a cutting remark…

Regardless, our perception continues patterning towards benefit, sometimes alighting on opportunities for freeing up some of this constraint. We notice how frequently we feel uneasy, and work through ideas about how to change this.

In the case of that gym membership we feel drawn to take up:

Maybe we need to seek out memetic support for this desire by subscribing to a Pinterest board of inspirational quotes. Those are easy to find, right?

Maybe we need a system for getting things done that can automatically remind us to go to the gym. We remember attending a seminar at work where somebody mentioned a system for getting things done…what was that called?3

Maybe we need to find an accountability buddy that will add to the dimensions of care available to us. Sven always talks about the gym, and he’s pretty friendly. Maybe we can ask Sven what gym he goes to next time we bump into him in the breakroom.

Maybe we can’t start that gym membership because of something we can work out in therapy. We’ve heard about remote therapy services in podcast advertisements. That seems kind of scary, and maybe a little suspicious, but maybe it’s worth trying out.

Maybe we’re especially interested in the basis of this problem—the constraint itself. We’ve heard people claim some meditation methods have lead them to liberated perception…maybe we’ll look into that.

There is no right answer here. Any of these paths may lead to freer perception and more powerful currents of care. The only way to find out is to try, and there is nothing wrong whatsoever with small steps.

Secure your own oxygen mask first

I highly recommend securing your own oxygen mask before you try to save anybody else. As I've alluded to, when we think we are acting for the benefit of others, we may really be acting for our own benefit—seeking to make ourselves feel just a little bit better for a little while. The wider the range of feelings we can accommodate without rejecting them, the more we begin to notice opportunities for providing care to others.

When we do feel basically okay—when we feel all-good, even—we may notice our minds moving with creative intent towards others’ benefit for its own sake. The surface area of beneficence can grow outward.

And regardless of the particulars of beneficial activity at any given point, we can recognize that everyone—ourselves included—are always doing this, at base.

I’m wary of such generalized statements about human nature. You should be, too. But reluctantly, I present this generalization about the basis of human nature:

Everyone is doing as well as they (believe they) can at the time.

There’s a great equality in this. Sometimes this means that another person is acting maliciously for their own gain at our expense, or at the expense of another. The same engine that drives this activity also drives our tolerance, our allowance, and/or our work to mercilessly oppose them.

As we work to oppose our political opponents, or as we scramble to get out of the way of an incoming political disaster, if we can recognize that everyone’s activity is the form their care has taken at that moment, we may find we are able to relax our existential angst, just a little bit.

I did not originally write this post about the U.S. election. But this event is too perfect an opportunity to apply the topic, so I’m editing and re-publishing this post. I’ll leave the original up to maintain continuity of the links I’ve created in other posts.

Concern, a form of care, is something I have often related to as an unwanted sensation. In other words, pain. Changing how we relate to sensation frees up perceptual constraint.

“Things” is a great app for this, available on Apple devices